The Philippines’ Post-Pandemic Phishing Problem – Part 1

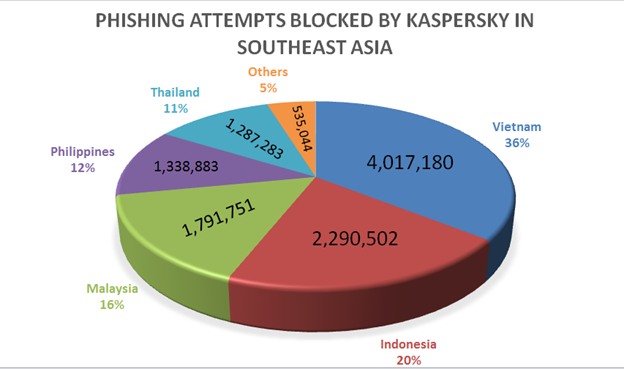

There is a phishing pandemic in the Philippines. Kaspersky’s Anti-Phishing system, according to Chris Connell, Managing Director for Asia Pacific at Kaspersky, blocked 1,338,883 phishing links in the Philippines in 2021 alone—a figure that accounts for about 10% of all phishing links Kaspersky blocked in all of Southeast Asia.

This problem of phishing has not only persisted in 2022, with the rise of smishing (SMS phishing). It has gotten so bad that lawmakers have gotten involved—a sure-fire indicator that an issue is officially a hot button. The Philippine Senate, in September, launched an inquiry into large-scale phishing and called on involved stakeholders to flesh out the problem. It also pushed hard for the ratification of the SIM Card Registration Act, a measure that will mandate users of Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) cards to register their number with their telco and, ostensibly, combat widespread phishing.

What Is Phishing?

Phishing is a type of cybercrime where cybercriminals posing as a legitimate institution, contact people via digital means, like email, telephone, or SMS (Short Message Service), so as to obtain from the latter their sensitive data, including personally identifiable information, banking details and passwords.

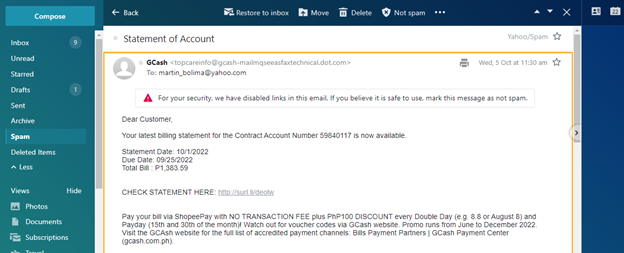

Consider this phishing attempt sent supposedly by GCash, a local digital wallet offered by Globe Telecom, one of the Philippines’ leading telcos. At first glance, everything appears legit. Upon closer inspection, there are red flags like the sender’s return address and the incongruence between the Statement Date (10/1/2022) and Date Due (9/25/2022). There is also the simple fact that GCash does not send emails of transaction histories unless the user requests it via the app.

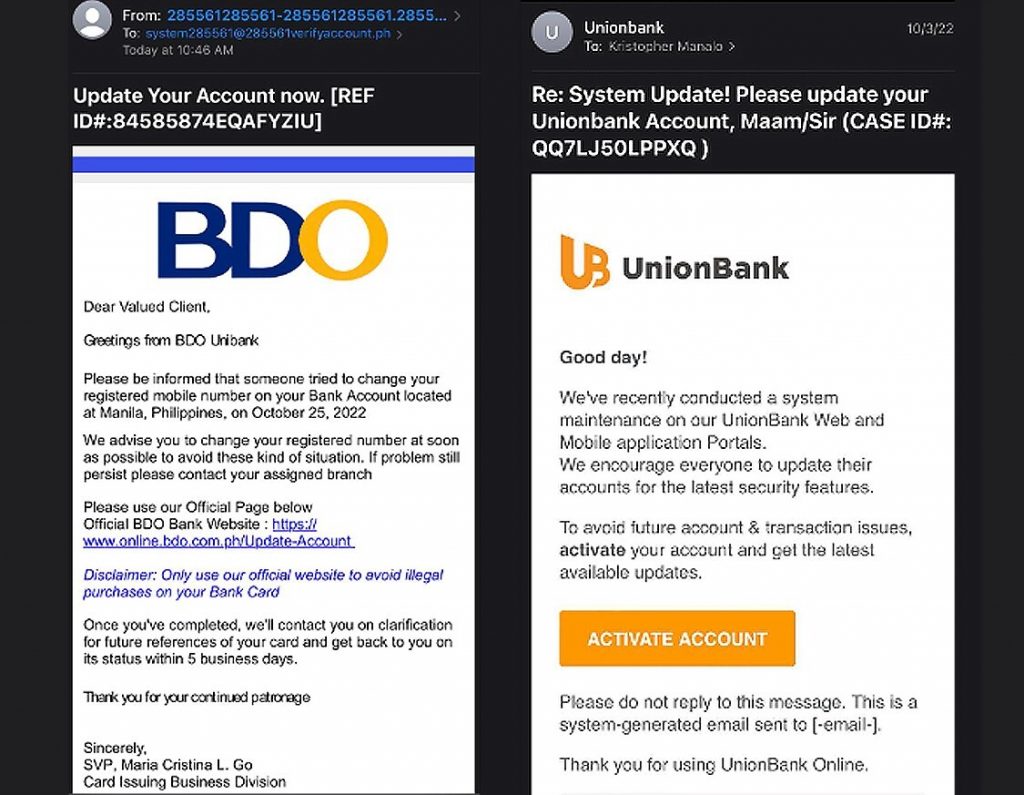

Then again, not everyone is able to distinguish between a legitimate email from a fraudulent one. This means that for every person who can spot a phishing attempt there is someone who may fall prey to it, more so if the phishing attempts are as believable as these two, sent supposedly by two of the Philippines’ largest banks, UnionBank and BDO:

“Phishing is most prevalent in cyber attack campaigns,” noted Chua Zong Fu, Vice President, Consulting at Ensign InfoSecurity, in an op-ed he wrote for Cybersecurity ASEAN (CSA) in March. “Due to its simplicity, ease of obtaining tools for attacks, and believability when exploiting human weaknesses, phishing remains one of the most effective methods to trick unsuspecting victims into providing sensitive information.”

In other words, phishing works just enough for cybercriminals to keep using it.

Smishing: The Evolution of Phishing

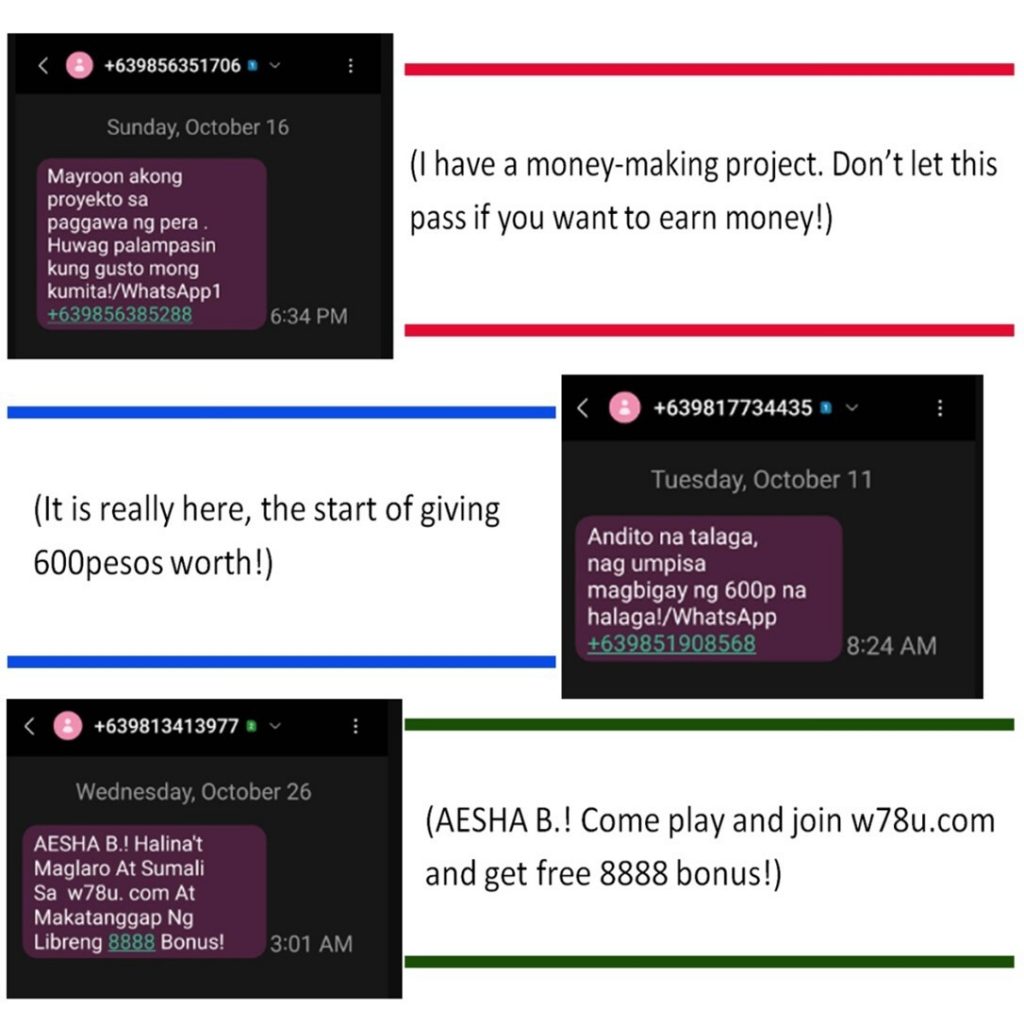

Exploiting human weaknesses is also the end-goal of smishing, an evolution of sorts of phishing in which the ruse described previously is done via SMS text messages, WhatsApp or similar messaging platforms. Consider these attempts:

“These smishing attacks often include fake claims for parcel delivery, alerts of disruptions to services or subscriptions or tempting promotions—urging the unsuspecting victims to click on malicious links…,” wrote Fu. “Smishing attempts also come with links to malicious websites that are made to look like legitimate websites, tricking users to enter their username and password details.”

The ruse is getting more sophisticated, with threat actors, for instance, registering domain names very similar to the domain names of legitimate companies (called “cousin domains”) in what is known as “typosquatting.” In other cases, cybercriminals might resort to Homoglyphs, or the use of deceptive or similar-looking characters to create hard-to-distinguish characters.

Whatever the strategies, phishing and smishing are swindling their fair share of victims—and it appears that many are trying to do just that in the Philippines (and in all of Southeast Asia).

Pandemic-Like Proportions

In the Philippines, smishing appears to have taken over phishing as the cybercriminals preferred mode to fish for sensitive information. In just two months (June–August), in fact, Smart Communications, Inc., the other major telco in the Philippines, claims to have blocked some 342 million smishing messages from 167,000 numbers, while its counterpart, Globe, says it has done much of the same.

But this was only after the National Telecommunications Commission, prompted by complaints from citizens and lawmakers, ordered telcos and relevant stakeholders to do more about this phishing/smishing pandemic. Who knows how many millions of these fraudulent texts were sent prior to this apparent crackdown—and how many more are getting through today? The answer is likely in the millions—millions already sent and millions still being sent.

This should not come as a surprise, said Kaspersky’s Connell, who took note of the 156.5 million cellular mobile connections in the Philippines at the start of 2022 and, as well as the country’s 76.01 million internet users as of January 2022. This high number of mobile and internet users and usage means more people are increasingly sharing their personal information online, thus resulting in “an enormous amount of personal information becoming vulnerable to cybercriminals.”

Curiously, it appears smishing had reached an inflextion point early in the year, to the point that the country’s major telcos had to start putting their foot down on the problem.

“During that time [early part of 2022], smishing was a fraud issue in Smart and PLDT. It was not a cybersecurity issue—not until it became so big that the leadership decided on June 5 to do something about it,” explained Angel Redoble, FVP & Group CISO at PLDT Group and Smart Communications and Cyber Defenders Council member.

Almost immediately, Smart suspended two data aggregators supposedly involved in sending smishing texts—and has remained on the lookout for suspicious activity from other similar groups. Redoble clarified, however, that neither Smart nor other telcos can do anything about person-to-person smishing, as telcos have no purview or jurisdiction over texts sent by one person to another. Neither do they have the capability to scrutinise person-to-person text messaging because it is against the law to do so.

So, while smishing has declined somewhat, it continues to be a problem (together with phishing)—so much so that every Filipino with a mobile phone and/or email account is at risk.

An Inconvenience With Potentially Major Implications

For many Filipinos, this pandemic of subterfuge has become an inconvenience. Imagine having to check your phone for a potentially important message, only to find a smishing text claiming you won a prize in a competition you never joined or asking you to redeem points from an app you never downloaded. Imagine that happening three, four, maybe five or six times a day. At some point, it is bound to be irritating, to say the least.

But be warned that phishing is legitimately a problem, and Oscar Visaya, Country Manager for the Philippines at Palo Alto Networks, offers this excellent analogy: “Phishing attacks are like mosquitoes, ubiquitous and annoying. And similar to mosquitoes, they are potential carriers of more dangerous threats, providing a gateway to ransomware or data exfiltration attacks.”

Meaning, for all the annoyance phishing can cause, it can do quite a lot of harm—a lot.

“As one of the main tactics used in successful data breaches today, there are many risks that come with falling victim to a phishing attack. It is typically deployed to steal data, money or both,” explained Visaya. “When a malicious link is clicked, via email or SMS, the cybercriminal may download malware onto the user’s device. This allows them to gain access to their sensitive information or potentially move laterally within the network to infect other devices. The threat actor may opt to sell the data to third parties for profit, hold it for ransom or destroy the victim’s or company’s data if demands aren’t met.”

Connell shares the same view, pointing out that phishing remains the method of choice of cyber criminals looking to infect users’ computers. Particularly vulnerable, according to Connell are corporate employees, whom he describes as “an easy entry into sensitive data.” And once cybercriminals obtain said data, they can then access a range of accounts—bank accounts, email inboxes, home networks, social media accounts and more.

This concludes part 1 of this two-parter. Join us for part 2, where we will take a look at why phishing and smishing are here to stay. But perhaps more importantly, we will take a look at what can be done to counter the threat.