Unmasking the World of Nation-State Cyber Threat Actors

We’re all experiencing the mounting pressure of today’s escalating cyber threats. However, how well-informed are we about the individuals lurking in the shadows, the very threat actors responsible for these malevolent acts?

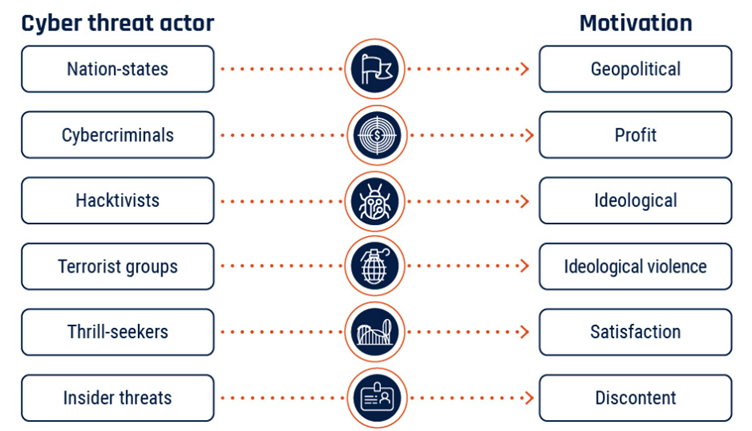

The world of cyber threat actors is a diverse landscape, with different motivations and varying levels of expertise. These actors can be classified based on their objectives and the sophistication of their techniques. Each category has its own primary motivation, driving its actions in the digital realm.

To facilitate a better comprehension, the accompanying picture illustrates the various categories of threat actors along with their respective motivations.

Cybersecurity companies have devised intriguing methods to identify threat actors. Scott Jarkoff, Director of Intelligence Strategy at CrowdStrike, reveals their approach of employing a two-part cryptonym that swiftly classifies adversaries based on their motives, using captivating designations such as:

Cybersecurity companies have devised intriguing methods to identify threat actors. Scott Jarkoff, Director of Intelligence Strategy at CrowdStrike, reveals their approach of employing a two-part cryptonym that swiftly classifies adversaries based on their motives, using captivating designations such as:

- SPIDERs: These cybercriminals are driven by monetary gain, operating with a profit-oriented agenda.

- Nation-states: Engaged in espionage, they are represented by the national animal of their respective countries. For instance, Russia is associated with BEAR, while China is symbolised by PANDA.

- JACKALS: These hacktivists seek to create political disruption, employing their cyber prowess to make a bold statement.

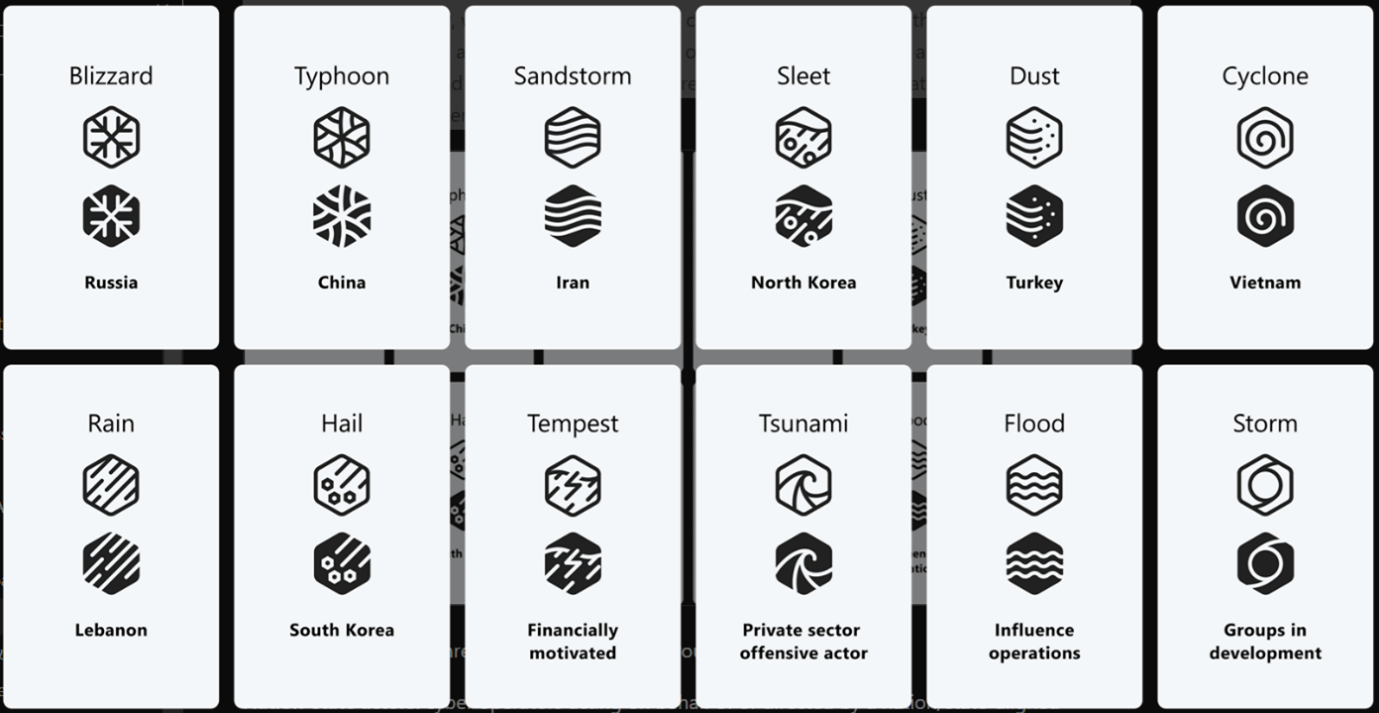

Microsoft on the other hand, has introduced a fascinating new naming system for threat actors based on weather themes, aiming to provide clarity and organisation in the overwhelming realm of threat intelligence. This taxonomy allows customers and security researchers to easily reference threat actors and prioritise their protection.

Here are the five key groups in Microsoft’s taxonomy:

- Nation-state actors: These are cyber operators working on behalf of or directed by a nation or state-aligned programme. They focus on traditional espionage or surveillance, targeting government agencies, intergovernmental organisations, think tanks, and non-governmental organisations.

- Financially motivated actors: These cyber campaigns are driven by criminal organisations or individuals seeking financial gain. This category includes ransomware operators, phishing groups, and those involved in business email compromise schemes.

- Private Sector Offensive Actors (PSOAs): Commercial actors create and sell cyberweapons to customers who then use them to target specific entities. These activities pose threats to human rights efforts and often target dissidents, journalists, human rights defenders, and civil society advocates.

- Influence operations: This category encompasses information campaigns, both online and offline, that aim to manipulate perceptions, behaviours, or decisions to further a group or nation’s interests.

- Groups in development: This designation is given to emerging or developing threat activities. It allows Microsoft to track them until sufficient information is gathered to identify the actor behind the operation. These groups are given a temporary designation of “Storm” along with a four-digit number.

Nation-state actors are associated with a country of origin, while other actors are identified based on their motivations. Adjectives are used to differentiate groups within the same weather family, indicating distinct tactics, techniques, procedures, objectives, or infrastructure.

These innovative approaches bring order to the complex landscape of threat actors, facilitating better understanding and proactive defence strategies.

Although exploring the various types of actors would be intriguing, the rest of this article will specifically delve deeper into the realm of nation-state actors, providing insights into their nature, motivations, and driving forces.

The Intricate Web of Nation-State Cyber Operations

It may sound like a plotline from a movie, but the reality is that nation-state actors pose a significant and imminent threat, often equipped with official authorisation to engage in hacking activities.

It may sound like a plotline from a movie, but the reality is that nation-state actors pose a significant and imminent threat, often equipped with official authorisation to engage in hacking activities.

These actors are employed by some governments with the explicit purpose of disrupting or compromising target government and defence sectors with the ultimate aim of obtaining sensitive intelligence, political secrets, and military capabilities by infiltrating governmental entities, according to Abhilash Purushothaman Vice President & General Manager, Asia, Rubrik. Their actions often have far-reaching international implications, underscoring the gravity of their operations.

Sumit Bansal, Vice President, Asia Pacific and Japan, BlueVoyant believes that there are two types of state-sponsored cyberattacks. The first is where aggressor states carry out targeted attacks against other nations that are deemed a threat, with the aim of causing as much operational or financial disruption as possible, usually while the aggressor state maintains full deniability. The second type is where cyberattacks are used within conflict with the same objectives – to cause as much disruption as possible, which may lead to weakened military capabilities. This is evident in Russia’s alleged targeting of private and public entities in Ukraine, during the ongoing invasion between the two countries.

Sumit Bansal, Vice President, Asia Pacific and Japan, BlueVoyant believes that there are two types of state-sponsored cyberattacks. The first is where aggressor states carry out targeted attacks against other nations that are deemed a threat, with the aim of causing as much operational or financial disruption as possible, usually while the aggressor state maintains full deniability. The second type is where cyberattacks are used within conflict with the same objectives – to cause as much disruption as possible, which may lead to weakened military capabilities. This is evident in Russia’s alleged targeting of private and public entities in Ukraine, during the ongoing invasion between the two countries.

These nation-state actors may operate as part of a clandestine “cyber army” or serve as “hackers for hire” for corporations aligned with the government’s agenda or a dictatorial regime. They are well aware of the chaos they sow abroad, knowing that their actions are implicitly supported by their home state. Shielded from legal consequences, they enjoy virtual immunity within their own country, making their arrest highly improbable.

Nation-state actors frequently maintain close ties with the military, intelligence agencies, or other government entities, boasting a high level of technical proficiency. Alternatively, they might recruit individuals based on specialised language skills, social media expertise, or cultural knowledge to engage in espionage, propaganda dissemination, or disinformation campaigns. Leveraging the vast resources and capabilities of their government, these actors take directives from government officials or military personnel.

Unveiling Motivations: Beyond Monetary Incentives

While cybercrime has undeniably emerged as a highly profitable pursuit, it is important to recognise that malicious actors are not always driven by financial motives. Many, especially nation-state actors, are after sensitive intellectual property or other sensitive and classified information, Jacqueline Jayne, Security Awareness Advocate, APAC, KnowBe4 mentioned.

While cybercrime has undeniably emerged as a highly profitable pursuit, it is important to recognise that malicious actors are not always driven by financial motives. Many, especially nation-state actors, are after sensitive intellectual property or other sensitive and classified information, Jacqueline Jayne, Security Awareness Advocate, APAC, KnowBe4 mentioned.

Nation-state actor is often or not, fuelled by intense nationalism, and is bestowed with formidable missions: to acquire classified information from rival nations or as countries increasingly shift towards internal manufacturing and development, it is highly probable that the targets of threat actors will evolve beyond espionage, encompassing deliberate disruptions to economic activities and operational infrastructures, suggests Nick Biasini, Head of Outreach, Cisco Talos.

Naturally, government agencies are top targets, but more often than not, attackers will look for a vulnerability in the supply chain, targeting governments’ systems through service providers that can provide a gateway to government systems. According to Tony Burnside, Vice-President Asia-Pacific, Netskope, this is precisely what Russian spies achieved with the SolarWinds supply chain attack, allowing them to roam US government systems undetected for months.

Digital supply chains are not exempt either as to what Chern-Yue Boey, Senior Vice President, APAC, SailPoint believes. “Given today’s interconnected business ecosystem, infiltrating one organisation can leave the security backdoor open for attacks on all other connected entities in the digital sphere,” he said.

The Wide-Ranging Impact of Nation-State Attacks

Jack Chubb, Head of Industrial Cybersecurity Middle East and Asia Pacific at Siemens Energy, mentioned that these threat actors comprehend the immense power and influence that comes with targeting energy systems. They set their sights on critical infrastructures like oil and gas facilities, electricity generation and distribution networks, and nuclear power plants.

Infiltrating these vital systems allows them to wreak havoc by disrupting operations, triggering economic turmoil, or even holding nations hostage. Picture oil and gas facilities, the lifeblood of global economies, being vulnerable to cyber intrusions aimed at crippling production, sabotaging supply chains, or manipulating energy prices. Similarly, adversaries may eye electricity systems that power entire countries, enticed by the potential to induce widespread blackouts and destabilise energy grids.

According to Gwen Lee, Regional Director for ASEAN at Armis and Richard Farrell, Asia Pacific Director of Digitalisation, Cloud and Data Centres Segment at Eaton, operational disruptions are on the rise with the healthcare facilities, particularly, being an attractive target for nation-state threat actors especially in times of heightened public health emergencies.

Moreover, Trellix’s Head of Threat Intelligence & Principal Engineer, John Fokker, together with Christophe Barel, Managing Director APAC, FS-ISAC gave the spotlight to the financial services industry as a frequent target for nation-state attacks due to the abundance of valuable data and potential for economic disruption. John Fokker believes that the fintech industry’s increased reliance on online banking, cloud technology, and remote work practices amplifies its susceptibility to cyberattacks.

Vicky Ray, Consulting Director at Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42, Asia Pacific & Japan, highlights the extensive reach of threat actors like BlackCat (aka ALPHV). Their impact spans diverse sectors including construction, retail, transportation, commercial services, insurance, machinery, professional services, telecommunications, auto components, and pharmaceuticals.

In 2020, Earth Longzhi, a subset of the well-known APT41, which is an advanced persistent threat group aligned with the Chinese nation-state, made its presence known. Satnam Narang, Senior Staff Research Engineer at Tenable, reveals that Earth Longzhi focused its attacks on multiple industries, including aviation, across Asian countries like Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Pakistan, as well as Ukraine.

The most disconcerting aspect of all this is that nation-state threat actors do not limit their targets to large corporations or countries alone. Over time, it has become evident that even Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) are not exempt from the threats posed by these actors.

Parvinder Walia, President for Asia Pacific and Japan at ESET explains that SMEs can be targeted as entry points to larger organisations through supply chain attacks. Lazarus, a North Korea-aligned APT group, as an example, compromised the software of VoIP communications company 3CX earlier this year, enabling malware distribution to specific customers. With over 600,000 customers in various sectors, including aerospace, healthcare, and hospitality, 3CX provides an extensive network of access points to high-value systems.

When taking all these factors into account, one must question the prospects of a small business or even an individual when faced with the formidable power of nation-state actors. These actors, backed by their governments and wholly dedicated to achieving their objectives, leave little room for optimism regarding the targeted entity’s ability to defend itself.

Forging a United Front

There is a saying, “As the adage goes, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link” and part of adversary targeting is understanding all the links in the chain to identify the weakest link.

This is why Christopher Budd, Senior Manager, Threat Research, Sophos believes that it is important for all organisations to understand their own unique threat profile so they can tailor their security posture appropriately. And part of that understanding includes recognising not just their threat profile but the threat profile of other organisations that they rely closely on so they can understand not just the direct risks but the indirect risks and identify when they are the weakest link in the chain and who the weakest links in their chains are.

Not only that, establishing an international standard of cyber risk management and response to nation-state threats remains an ongoing objective. The transnational nature of these threats requires a global approach involving cross-border, real-time intelligence sharing and robust cyber resilience. Cooperation and collaboration among government agencies, regulatory bodies, and industry organisations are also vital to establishing consistent cybersecurity frameworks, information-sharing mechanisms, and legal frameworks to deter and mitigate nation-state cyber threats.

Information-sharing communities are essential for countering nation-state threat actors. They facilitate intelligence exchange, collaboration, and best practice dissemination. Through pooling resources and knowledge, organisations strengthen their defences, anticipate attacks, and develop effective countermeasures. These communities also serve as early warning systems and contribute to policy development for a robust cyber defence ecosystem.

Dear readers, as we navigate the complexities of the digital age, it is imperative to recognise the impact of nation-state threat actors and forge a united front against their malicious activities. Only through collective resilience and a steadfast commitment to cybersecurity can we ensure a future where the power of the digital realm is harnessed for progress, innovation, and the betterment of society.