Don’t Get Mad, Get Wise

The “Mad Liberator” ransomware group leverages social-engineering moves to watch out for

Written by: Paul Jacobs and Lee Kirkpatrick from Sophos

The Sophos X-Ops Incident Response team has been examining the tactics of a ransomware group called Mad Liberator. This is a fairly new threat actor, first emerging in mid-July 2024. In this article, we’ll look at certain techniques the group is using, involving the popular remote-access application Anydesk. We’ll document the interesting social-engineering tactics the group has used and provide guidance both as to how to minimize your risk of becoming a victim and, for investigators, how to see potential activity by this group.

Before we start, we should note that Anydesk is legitimate software that the attackers are abusing in this situation. The attackers misuse that application in the manner we’ll show below, but presumably, any remote access program would suit their purposes. Also, we’ll note up front that SophosLabs has a detection in place, Troj/FakeUpd-K, for the binary described.

What is Mad Liberator?

The activity that Sophos X-Ops has observed so far indicates that Mad Liberator focuses on data exfiltration; in our own experience, we have not yet seen any incidents of data encryption traceable to Mad Liberator. That said, information on watchguard.com does suggest that the group uses encryption occasionally, and also undertakes double extortion (stealing data, then encrypting the victim’s systems and threatening to release the stolen data if the victim doesn’t pay to decrypt).

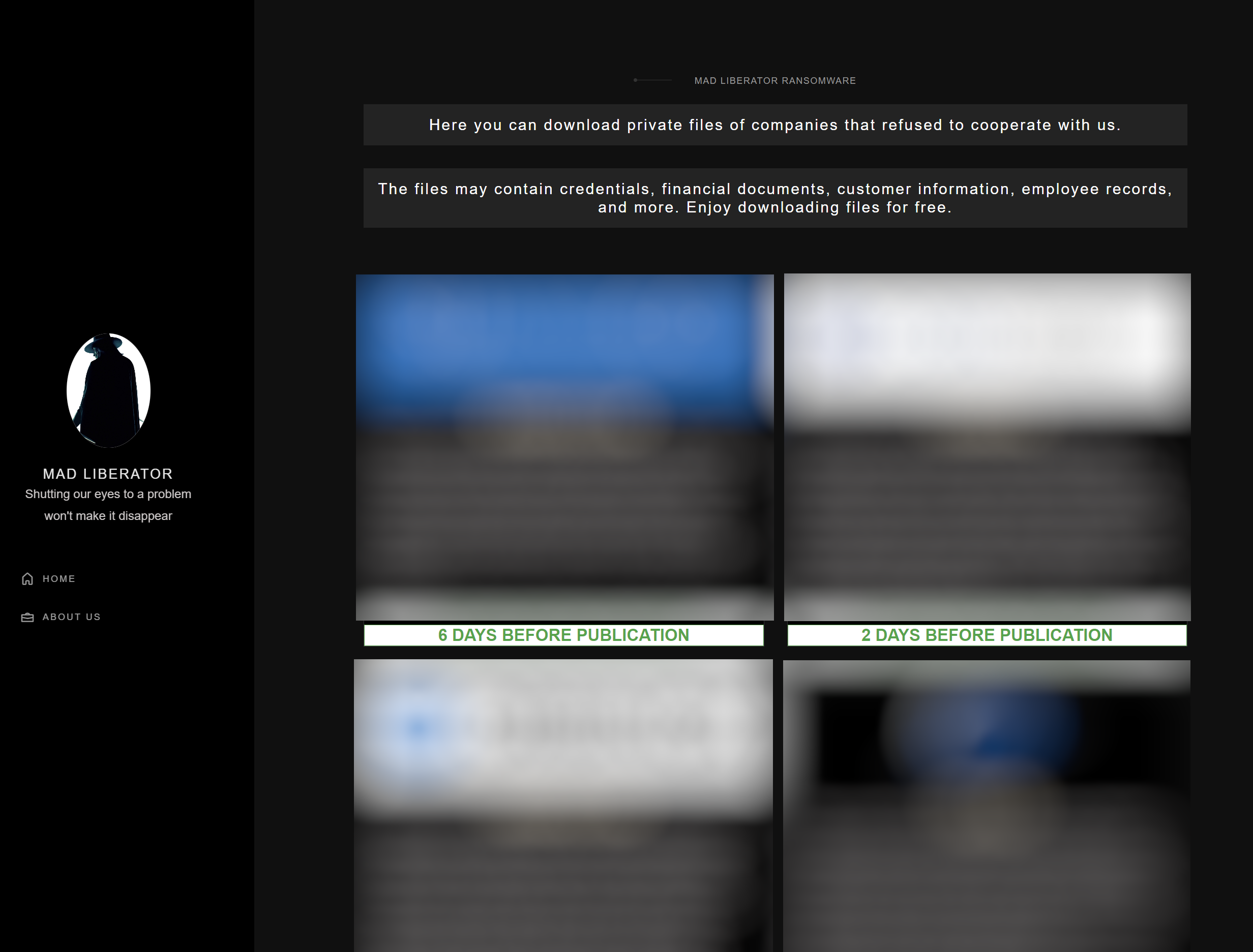

Typical of threat actors who perform data exfiltration, Mad Liberator operates a leak site on which it publishes victim details, in an effort to put additional pressure on victims to pay. The site claims that the files can be downloaded “for free.”

Interestingly, Mad Liberator uses social engineering techniques to obtain environment access, targeting victims who use remote access tools installed on endpoints and servers. Anydesk, for instance, is popularly used by IT teams to manage their environments, particularly when working with remote users or devices.

How the Attack Works

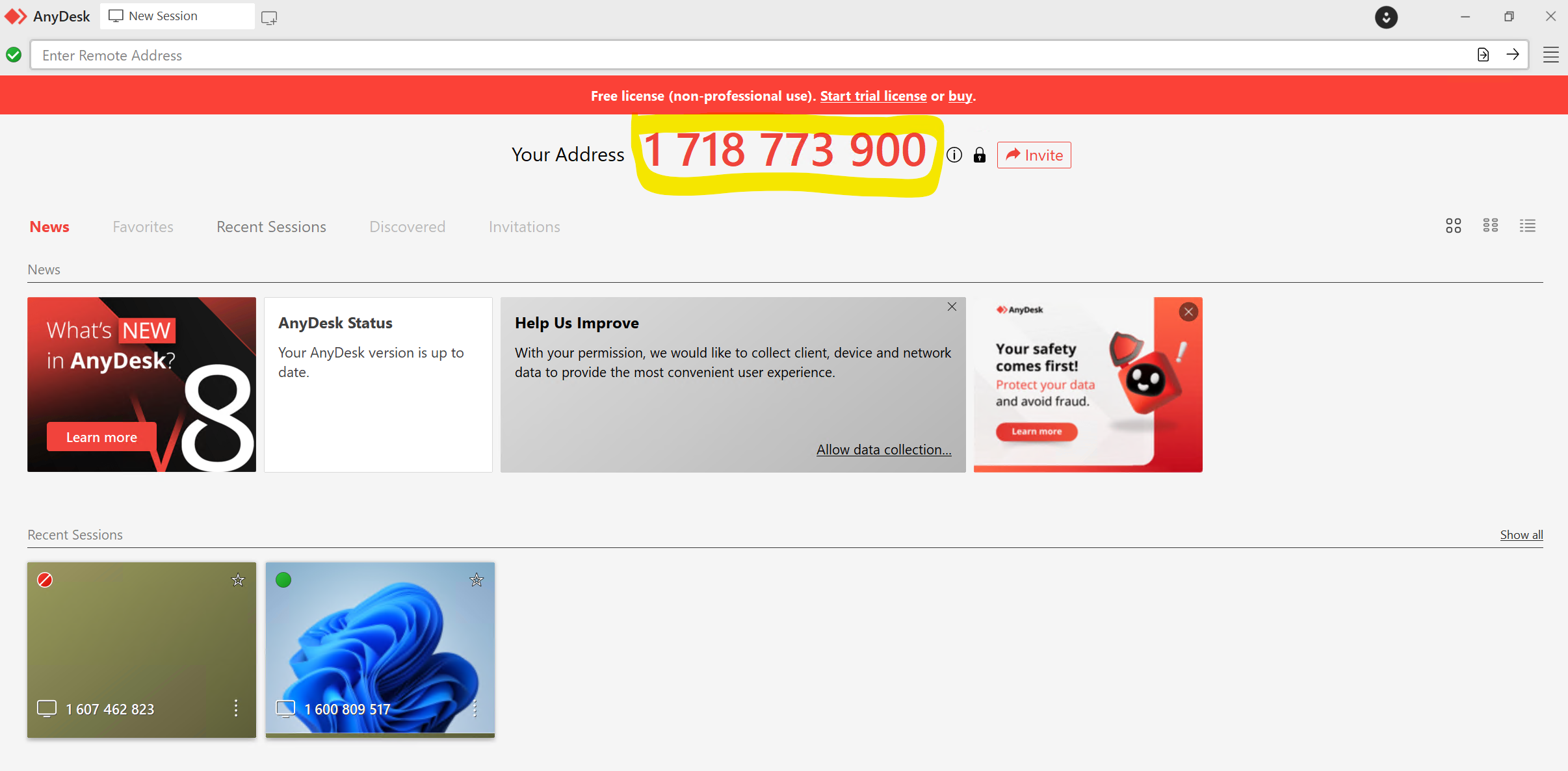

Anydesk works by allocating a unique ID, in this case a ten-digit address, to each device it is installed on. Once the application is installed on a device, a user can either request to access a remote device to take control by entering the ID, or a user can invite another user to take control of their device via a remote session.

We don’t know at this point how, or if, the attacker targets a particular Anydesk ID. In theory, it is possible to just cycle through potential addresses until someone accepts a connection request; however, with potentially 10 billion 10-digit numbers, this seems somewhat inefficient. In an instance that the Incident Response team investigated, we found no indications of any contact between the Mad Liberator attacker and the victim prior to the victim receiving an unsolicited Anydesk connection request. The user was not a prominent or publicly visible member of staff and there was no identifiable reason for them to be specifically targeted.

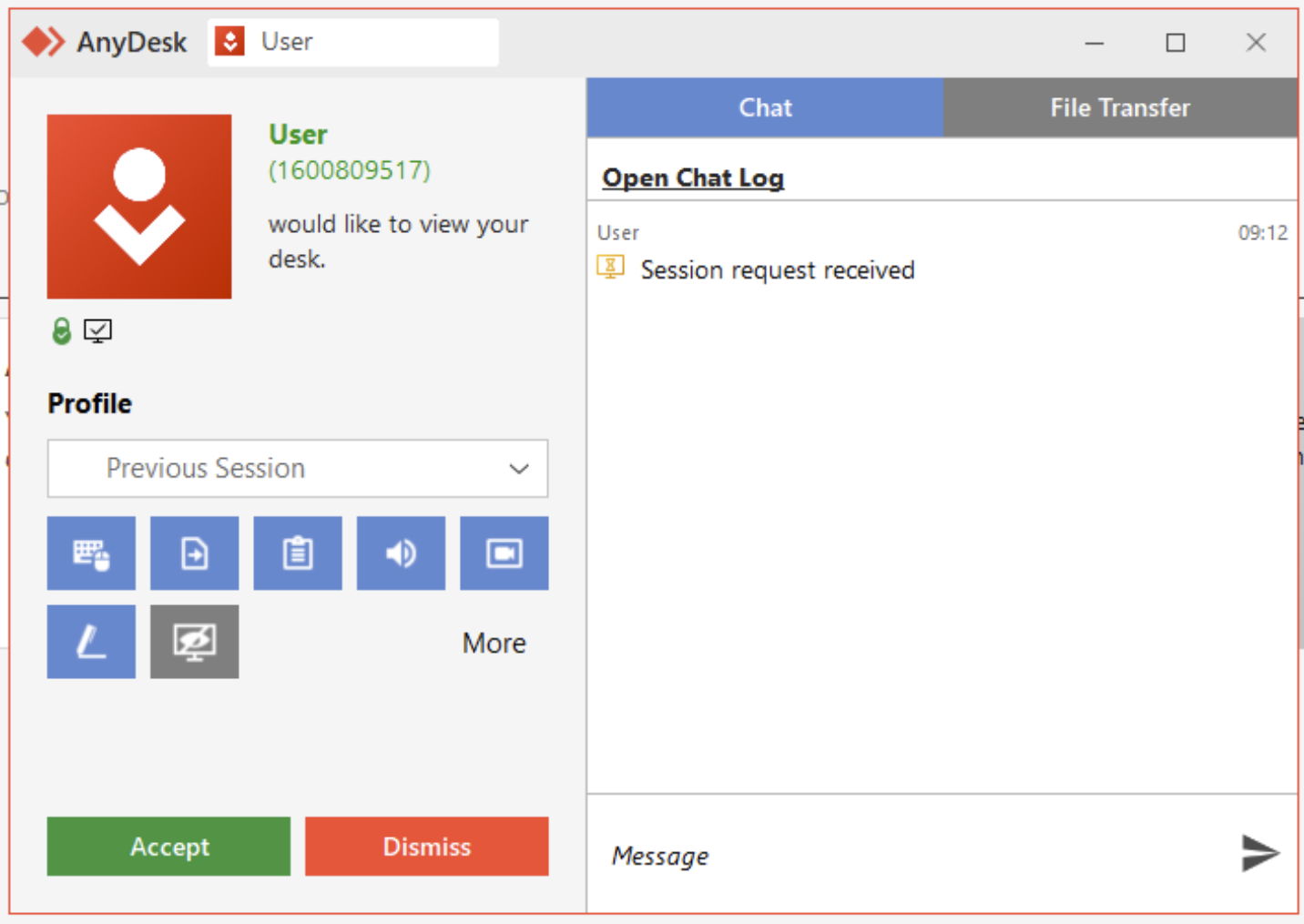

When an Anydesk connection request is received, the user sees the pop-up shown in Figure 3. The user must authorise the connection before it can be fully established.

In the case our IR team handled, the victim was aware that Anydesk was used by their company’s IT department. They therefore assumed that the incoming connection request was just a usual instance of the IT department performing maintenance, and so clicked Accept.

Once the connection was established, the attacker transferred a binary to the victim’s device and executed it. In our investigations, this file has been titled “Microsoft Windows Update,” with the SHA256 hash:

f4b9207ab2ea98774819892f11b412cb63f4e7fb4008ca9f9a59abc2440056fe

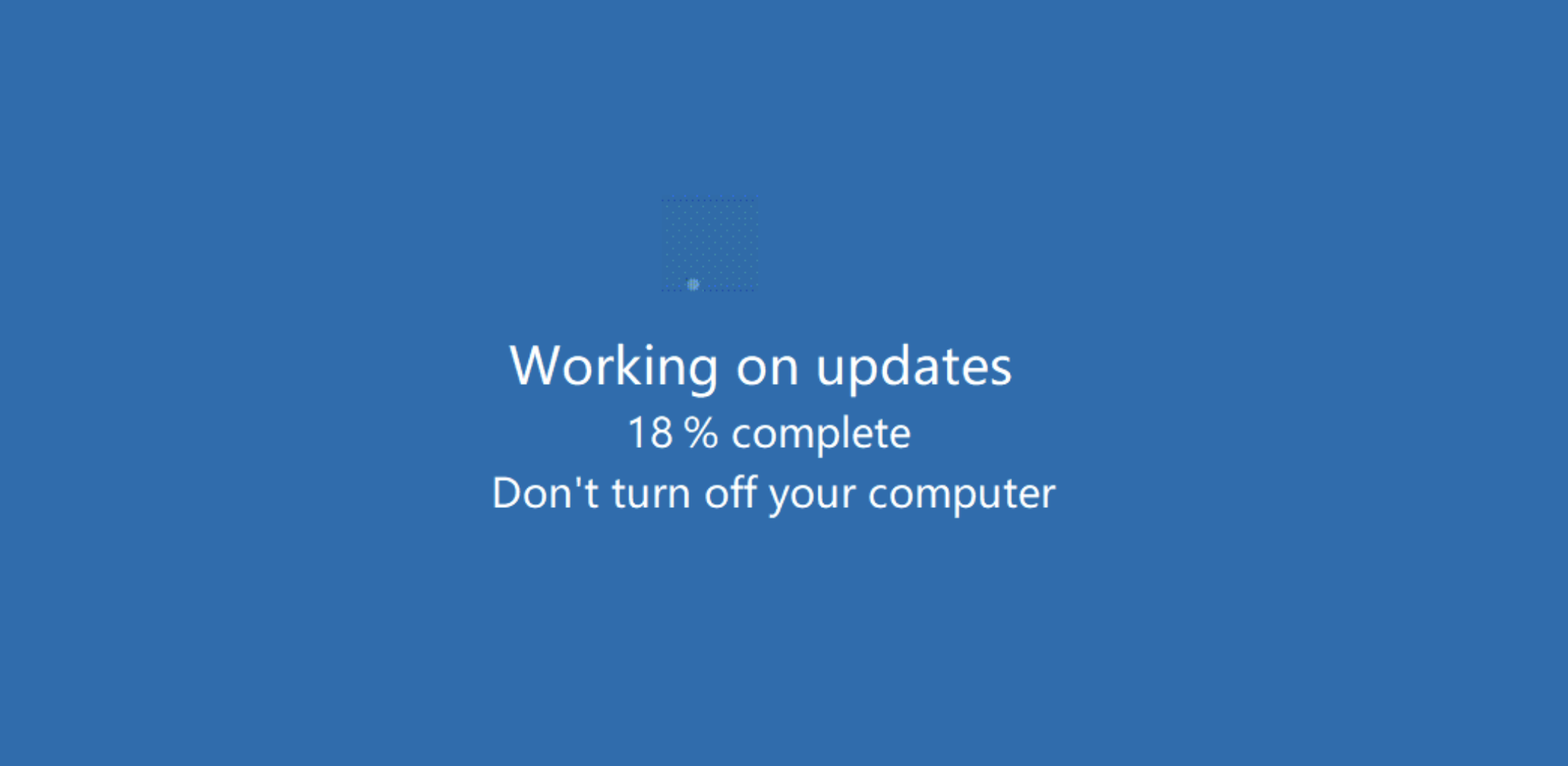

This binary was a very simple program that displayed a splash screen mimicking a Windows Update screen. The screen was animated, making it appear that the system was updating, as shown in Figure 4.

This program did not perform any other activity, which made it unlikely to be immediately detected as malicious by most antimalware packages. (Sophos has developed a detection [Troj/FakeUpd-K] for this particular binary and will continue to monitor developments on this.)

At this point, to protect the ruse from being discovered and stopped, the attacker took an extra step. Since this simple program could have been exited should the user happen to press the “Esc” key, the attacker utilized a feature within Anydesk to disable input from the user’s keyboard and mouse.

Since the victim was no longer able to use their keyboard, and since the above screen appeared to be something unremarkable to any Windows user, they were unaware of the activity that the attacker was performing in the background – and could not have stopped it easily even if they were suspicious.

The attacker proceeded to access the victim’s OneDrive account, which was linked to the device, as well as files that were stored on a central server and accessible via a mapped network share. Using the Anydesk FileTransfer facility, the attacker stole and exfiltrated these company files. The attacker then used an Advanced IP Scanner to determine if there were other devices of interest that could be exploited within the same subnet. (They did not, in the end, laterally move to any other devices.)

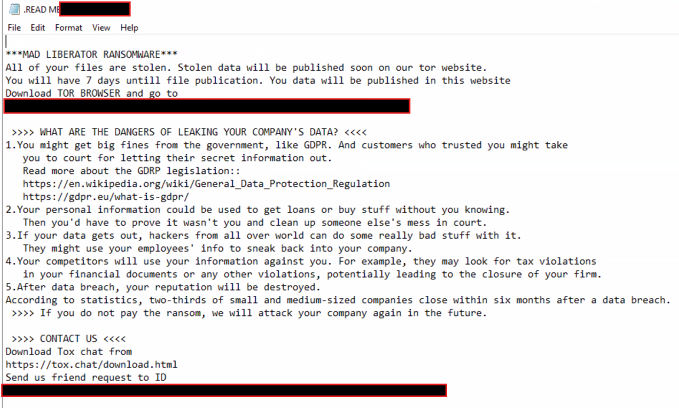

Once the stolen files were under its control, the attacker then ran another program that created numerous ransom notes. Interestingly, these ransom notes were generated in multiple locations on a shared network location which was mapped to the device, rather than to the victim’s device itself. These ransom notes announced that data had been stolen and provided details as to how the victim should pay the ransom to prevent disclosure of those stolen files. (Tactics such as these will be all too familiar to readers of our investigation of pressure tactics currently in use by ransomware gangs.)

The fake Windows Update screen shielded the attacker’s actions from being seen on the victim’s screen. The attack lasted almost four hours, at the conclusion of which the attacker terminated the fake update screen and ended the Anydesk session, giving control of the device back to the victim. We did note that the binary was manually triggered by the attacker; with no scheduled task or automation in place to execute it again once the threat actor was gone, the file simply remained on the affected system.

Lessons and Mitigations

This was a straightforward attack that relied on the victim believing that the Anydesk request was part of day-to-day activity. As far as our investigators could determine, the attack did not involve any additional social engineering efforts by the attacker — no email contact, no phishing attempts, and so forth. As such it highlights the importance of ongoing, up-to-date staff training, and it indicates that organizations should set and make known a clear policy regarding how IT departments will contact and arrange remote sessions.

Beyond user education, we highly recommend that administrators implement the Anydesk Access Control Lists to only allow connections from specific devices in order to greatly minimize the risk of this type of attack, AnyDesk provides some very valuable guidance and how to do this as well as additional security measures in the following link:

With additional advice is available here:

- https://blog.anydesk.com/the-ultimate-guide-to-anydesks-security-features/

- https://anydesk.com/en/security

Procedural notes for investigators follow the conclusion of this article.

Conclusion

Ransomware groups rise and fall constantly, and Mad Liberator may prove to be a significant new player or just another flash in the pan. However, the social-engineering tactics the group used in the case described above are noteworthy – but they are not unique. Attackers will always continue to develop and employ a variety of tactics to try and exploit both the human element and the technical security layers.

It can be a difficult task to balance security against usability when implementing tools within an environment, especially when these tools help facilitate remote access for the very people tasked with caring for business-critical systems. However, we always recommend that when applications are deployed across a network, especially ones that can be leveraged to obtain remote access to devices, that careful review of the security recommendations by the vendor is considered. Where those recommendations are not followed, that choice should be documented as part of your risk management process so that it can be continually reviewed, or so other mitigations can be put in place to ensure it remains within the risk appetite of your organization.